The Effects on Brain Development

"Our brains are sculpted by our early experiences. Maltreatment is a chisel that shapes a brain to contend with strife, but at the cost of deep, enduring wounds." -- Teicher, 2000, p.67 |

In recent years, there has been a surge of research into early brain development. As recently as the 1980s, many professionals thought that by the time babies were born, the structure of their brains was already genetically determined. The role of experience on the developing brain structure was under-appreciated, as was the active role of babies in their own brain development through interaction with their environment (Shore, 1997). While much of the research examining brain functioning has been done with animals, new technologies are enabling more non-invasive research to be done with humans. Although there is still much to learn, we now know much more about the brain's development and functioning.

One area that has been receiving increasing research attention involves the effects of abuse and neglect on the developing brain during infancy and early childhood. Much of this research is providing biological explanations for what practitioners have been describing in psychological, emotional, and behavioral terms. We are beginning to see the scientific "evidence" of altered brain functioning as a result of early abuse and neglect. This emerging body of knowledge has many implications for the prevention and treatment of child abuse and neglect.

HOW THE BRAIN DEVELOPS

What we have learned about the process of brain development has helped us understand more about the influence of genetics and environment on our total development--the "nature versus nurture" debate. It appears that genetics predispose us to develop in certain ways. But our interactions with our environment have a significant impact on how our predisposition will be expressed; these interactions organize our brain's development and, therefore, shape the person we become (Shore, 1997).

Forming the Structure

The raw material of the brain is the nerve cell, called the neuron. When babies are born, they have almost all of the neurons they will ever have -- more than 100 billion of them. Although there is research that indicates some neurons are developed after birth and well into adulthood (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000), the neurons babies have at birth are primarily what they have to work with as they develop into children, adolescents, and adults.

During fetal development, the neurons that are created migrate to form the various parts of the brain. While the basic structure is intact at birth, much of the brain's growth occurs during the first few years after birth. This process of growth, or development, occurs sequentially from the "bottom up" (Perry, Pollard, Blakely, Baker & Vigilante, 1995; Perry, 2000a).

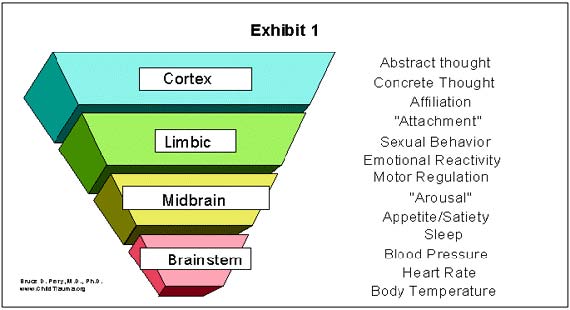

The first areas of the brain to develop fully are the brainstem and midbrain; they govern the bodily functions necessary for life, called the autonomic functions. The last regions of the brain to develop fully are the limbic system, involved in regulating emotions, and the cortex, involved in abstract thought. (See Exhibit 1.) Each region manages its assigned functions through complex processes, often using chemical messengers (such as neurotransmitters and hormones) to help transmit information to other parts of the brain and body (Perry, Pollard, Blakely, Baker & Vigilante, 1995; Perry, 2000a).

|

As the brain develops, it grows larger and denser. By the age of 3, a baby's brain has reached almost ninety percent of its adult size (Perry, 2000c). The growth in each region of the brain largely depends on receiving stimulation, which spurs activity in that region. This stimulation provides the foundation for learning.

Prenatal Exposure to Alcohol & Other Drugs

Exposure to alcohol and other drugs in utero can disrupt and significantly impair the way a baby's brain is formed (Shore, 1997).

Studies have shown that exposure to alcohol or other drugs, especially early in pregnancy, can alter the development of the cortex, reduce the number of neurons that are created, and affect the way in which chemical messengers are used (Shore, 1997). Although not all children who are exposed develop neurobiological problems, many do. These problems include difficulties with attention, memory, problem solving, and abstract thinking. Many children born with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome are mentally retarded (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000).

Organizing the Structure

Brain development, or learning, is actually the process of creating, strengthening, and discarding connections among the neurons; these connections are called synapses. Synapses organize the brain by forming neuronal pathways that connect the parts of the brain governing everything we do -- from breathing and sleeping to thinking and feeling. This is the essence of post-natal development, because at birth, very few synapses have been formed. The synapses present at birth are primarily those that govern our bodily functions such as heart rate, breathing, eating, and sleeping. Almost all other functions are developed as babies grow up into children and adults (Shore, 1997).

The development of synapses occurs at an astounding rate during children's early years. By the time children are 3, their brains have approximately 1,000 trillion synapses, many more than they will ever need. Some of these synapses are strengthened and remain intact, but many are discarded. By the time children have reached adolescence, about half of their synapses have been discarded, leaving about 500 trillion, the number they will have for most of the rest of their lives (Shore, 1997).

Plasticity – The Influence of Environment

"Plasticity is a double-edged sword that leads to both adaptation and vulnerability." -- Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000, p. 94 |

Researchers use the term plasticity to describe the way the brain creates, strengthens, and discards synapses and neuronal pathways in response to the environment (Ounce of Prevention Fund, 1996). The brain's "plasticity" is the reason that environment plays a vital role in brain development.

The early over-production of synapses appears to be the result of evolution that has led our brains to expect certain experiences (Greenough, Black & Wallace, 1987). Our brains prepare us for these experiences by forming the pathways needed to respond to those experiences. For example, our brains are "wired" to respond to the sound of speech; this is how we learn to talk. But these early synapses are weak; we must repeatedly be exposed to the expected experiences within a certain time period to activate and strengthen them. If this does not happen, the pathways developed in anticipation of those experiences may be discarded, and the development of the related functions will not occur as expected. This is often referred to as the "use it or lose it" principle (Greenough, Black & Wallace, 1987).

In addition to strengthening or discarding existing synapses, researchers theorize that some synapses may be newly developed in response to unique environmental conditions (Greenough, Black & Wallace, 1987). It is through these processes of creating, strengthening, and discarding synapses that our brains adapt each of us to our unique environment.

The ability to adapt to our environment is a part of normal development. Children growing up in cold climates or on rural farms or in large sibling groups learn how to function in those environments. But regardless of the general environment, all children need stimulation and nurturance for healthy development. If these are lacking -- if a child's caretakers are indifferent or hostile -- the child's brain development may be impaired. Because the brain adapts to its environment, it will adapt to a negative environment just as readily as it will adapt to a positive environment.

Sensitive Periods

"It is now clear that what a child experiences in the first few years of life largely determines how his brain will develop and how he will interact with the world throughout his life." -- Ounce of Prevention Fund, 1996 |

Researchers believe that during these years there may be "sensitive periods" for development of certain capabilities (Greenough, Black & Wallace, 1987). Because synapses are being formed at such an intense pace during this time, the opportunities for learning are almost limitless. But as the process of pruning synapses starts to increase, especially after age 3, these opportunities begin to decrease (Shore, 1997). If certain synapses and neuronal pathways are not repeatedly activated, they may be discarded, and the capabilities they promised may be diminished. For example, all infants have the capacity, indeed the genetic predisposition, to form strong attachments to their primary caregivers. But if a child's caregivers are unresponsive or threatening, and the attachment process is disrupted, the child's ability to form any healthy relationships during his or her life may be impaired (Perry, 2001a).

Although the first few years may be the "prime time" for learning, children and adults can learn later in life, but it is more difficult. This is especially true if a young child was deprived of certain stimulation, which resulted in the pruning of synapses and the loss of neuronal pathways. Helgeson (1997) offers the analogy of a country that has a dense network of branching streets; a traveler can go anywhere he wants, even unfamiliar places, by following the roads. If there are few roads, the traveler can still go places, but he has to travel "cross-country" and break new ground. It is doable, but much harder. As children progress through each developmental stage, they will learn and master each step more easily if their brains have built an efficient network of pathways.

Malnutrition

Malnutrition, both before and during the first few years after birth, has been shown to result in stunted brain growth and slower passage of electrical signals in the brain (Pollitt & Gorman, 1994; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000). These effects on the brain are linked to cognitive, social, and behavioral deficits with possible long-term consequences (Karr-Morse & Wiley, 1997).

For example, iron deficiency (the most common form of malnutrition in the United States) can result in cognitive and motor delays, anxiety, depression, social problems, and problems with attention (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000). Protein deficiency can result in motor and cognitive delays and impulsive behavior (Pollitt & Gorman, 1994). The social and behavioral impairments may be more difficult to "repair" than the cognitive impairments, even if the nutritional problems are corrected (Karr-Morse & Wiley, 1997).

While research has shown that the brain is more malleable in the first few years than at any other time in life, researchers disagree on how flexible or rigid the sensitive periods are. But they do agree that the experiences of the first few years form the foundation for children's future functioning. "While experiences may alter and change the functioning of an adult, experience literally provides the organizing framework for an infant and child" (Perry, Pollard, Blakely, Baker & Vigilante, 1995).

Memories

The "organizing framework" for children's development is based on the creation of "memories." When repeated experiences strengthen a neuronal pathway, the pathway becomes "sensitized," and, at some point, it becomes a memory. Memories are an indelible impression of the world (Perry, 1999); they are the way in which the brain stores information for easy retrieval.

There are different types of memories, such as motor, cognitive, and emotional memories. Memories help us to navigate our world without having to really think about it (Perry, 1999). Children learn to put one foot in front of the other to walk. They learn words to express themselves. And they learn that a smile usually brings a smile in return. At some point, they no longer have to think much about these processes -- their brains manage these experiences with little effort because the memories that have been created allow for a smooth, efficient flow of information.

The creation of memories is part of our adaptation to our environment. Our brains attempt to understand the world around us and fashion our interactions with that world in a way that promotes our survival and, hopefully, our growth. But if the early environment is abusive or neglectful, our brains will create memories of these experiences that may adversely color our view of the world throughout our life.