Explicit Instruction

Introduction

The teaching practice of explicit instruction has been available to educators since the late 1960s. Explicit instruction, also known as direct instruction, has been shown to be efficacious in learning and teaching the major components of academic skills instruction (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000). Substantial research has been conducted on its components and the complete instructional “package.” As with many teaching practices, there are varying degrees of adaptation and acceptance. However, the great majority favor the outcomes for students taught using explicit instruction. Research on effective teaching practices has identified most—if not all—of the components of explicit instruction as essential for positive student outcomes (e.g., Rosenshine & Stevens, 1986; Ellis & Worthington, 1995). Explicit instruction embodies the entire instructional/assessment cycle including planning and design, delivery and management, and evaluation/assessment. As noted by Archer and Hughes (2011), instruction that is designed to be explicit is characterized by three essential stages: (a) clear delivery with models and demonstrations, followed by (b) guided practice supported by the teacher with corrective feedback delivered in a timely manner, and finally (c) gradual withdrawal of teacher supports during practice to move students toward independent performance. Objectives that students are to learn often require differing degrees of directness and structure, and explicit instructional strategies are dynamic and interactive in a relationship that mandates flexible and responsive instruction (Villaume & Brabham, 2003).

Definition

Explicit instruction is a systematic instructional approach that includes set of delivery and design procedures derived from effective schools research merged with behavior analysis. There are two essential components to well-designed explicit instruction: (a) visible delivery features consisting of group instruction with a high level of teacher and student interactions and (b) the less observable instructional design principles and assumptions that make up the content and strategies to be taught.

Explicit instruction practices bring together highly recognized and recommended components of effective instruction and of schema theory. These include providing step-by-step explanations, modeling, engaging in guided practice; practicing the skill or element independently in a variety of applications; support in making connections of new to previous learning; teacher explanations as to the importance, usefulness, and relationships of a new skill or cognitive strategy; and consistently eliciting student interest (Rupley, Blair, & Nichols, 2009).

The “direct [explicit] instruction model is a comprehensive system of instruction that integrates effective teaching practices with sophisticated curriculum design, classroom organization and management, and careful monitoring of student progress, as well as extensive staff development” (Stein, Carnine, & Dixon, 1998). The primary goal of direct instruction is to increase not only the amount of student learning but also the quality of that learning by systematically developing important background knowledge and explicitly applying it and linking it to new knowledge.

Identifying Components

Explicit instruction consists of essential—

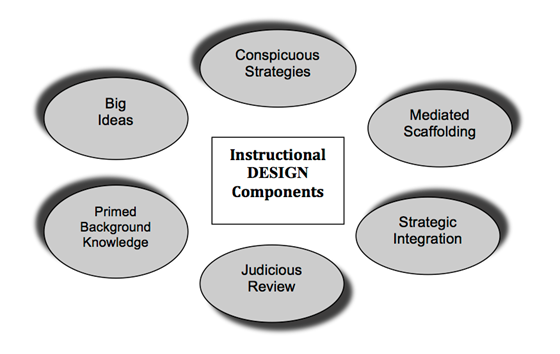

Standard Instructional Design Components

Essential to All Explicit Instructional Episodes

Big Ideas

Big ideas function as the keys that unlock content for a range of diverse learners. Those concepts, principles, or heuristics facilitate the most efficient and broadest acquisition of knowledge. Teaching using big ideas is one promising means of striking a reasonable balance between unending objectives and no objectives at all.

Conspicuous Strategies

People accomplished at complex tasks apply strategies to solve problems. Empirical evidence suggests that all students in general, and diverse learners in particular, benefit from having good strategies made conspicuous for them. This, paired with great care taken to ensure that the strategies are well-designed, result in widely transferable knowledge of their application.

Mediated Scaffolding

This temporary support/guidance is provided to students in the form of steps, tasks, materials, and personal support during initial learning that reduces task complexity by structuring it into manageable chunks to increase successful task completion. The degree of scaffolding changes with the abilities of the learner, the goals of instruction, and the complexities of the task. Gradual and planned removal of the scaffolds occurs as the learner becomes more successful and independent at task completion. Thus, the purpose of scaffolding is to allow all students to become successful in independent activities. There are at least two distinct methods to scaffold instruction; teacher assistance and design of the examples used in teaching.

Strategic Integration

The instructional design component of strategic integration combines essential information in ways that result in new and more complex knowledge. Characteristics of strategic instruction include a) curriculum design that offers the learner an opportunity to successfully integrate several big ideas, b) content to be learned must be applicable to multiple contexts, and c) potentially confusing concepts and facts should be integrated once mastered. The strategic integration of content in the curriculum can help students learn when to use specific knowledge beyond classroom application.

Judicious Review

Effective review promotes transfer of learning by requiring application of content at different times and in different contexts. Educators cannot assume that once a skill is presented and “in” the learner’s repertoire that the skill or knowledge will be maintained. Intentional review is essential to ensure that students maintain conceptual and procedural “grasp” of important skills and knowledge (big ideas). Judicious review requires that the teacher select information that is useful and essential. Additionally, review should be distributed, cumulative, and varied. Requirements for review will vary from learner to learner. To ensure sufficient judicious review for all learners, teachers must regularly monitor progress of the students to inform continued instruction and needed review activities. Review that is distributed over time, as opposed to massed in one learning event, contributes to long-term retention and problem solving.

Primed Background Knowledge

Acquisition of new skills and knowledge depends largely upon a) the knowledge the learner brings to the task, b) the accuracy of that information, and c) the degree to which the learner can access and use that information. Priming background knowledge is designed to strategically cultivate success by addressing the memory and strategy deficits learners may bring to the new task. The functions of priming background knowledge are to increase the likelihood that students will be successful on new tasks by making critical features explicit and to motivate learners to access knowledge they have in place.

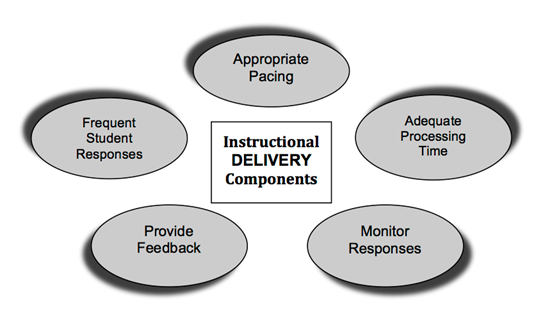

Standard Instructional Delivery Components

Essential to All Explicit Instructional Episodes

Require frequent student responses

When students actively participate in their learning, they achieve greater success. The teacher must elicit student responses several times per minute: for example, ask students to say, write, or do something. Highly interactive instructional procedures keep students actively engaged, provide students with adequate practice, and help them achieve greater success.

Appropriate instructional pacing

Pacing is the rate of instructional presentations and response solicitations. The pace of instruction is influenced by many variables such as task complexity or difficulty, relative newness of the task, and individual student differences. When tasks are presented at a brisk pace, three benefits to instruction are accomplished: (a) students are provided with more information, (b) students are engaged in the instructional activity, and (c) behavior problems are minimized (students stay on-task when instruction is appropriately paced).

Provide adequate processing time

Thinking time (adequate processing time) is the amount of time between the moment a task is presented and when the learner is asked to respond. Time to pause and think should vary based on the difficulty of the task relative to the student(s). If a task is relatively new, the amount of time allocated to think and formulate a response should be greater than that of a task that is familiar and in the learners’ repertoire.

Monitor responses

This is an essential teacher skill to ensure that all learners are mastering the skills the teacher is presenting. Watching and listening to student responses provides the teacher with key instructional information. Adjustments may be made during instruction. Teachers should be constantly scanning the classroom as students respond in any mode.

Provide feedback for correct and incorrect responses

Students should receive immediate feedback to both correct and incorrect responses. Corrective feedback needs to be instructional and not accommodating. Feedback to reinforce correct responses should be specific. Feedback should not interfere with the timing of the next question/response interaction of the teacher and student. Feedback that does not meet these criteria can interrupt the instructional episode and disrupt the learner’s ability to recall.

Implications for Access to the General Curriculum

“Declarative, procedural and conditional knowledge are necessary ingredients for strategic behavior. Students can learn about these features of reading through direct instruction as well as by practice. Part of a teacher’s job is to explicate strategies for reading so that students will perceive them as useful and sensible” (Paris, l986).

Programs using explicit instruction have been researched extensively across classrooms by grade (pre-school through adult) and by ability (special and general education settings) since the mid-1960s. General education classrooms in these studies were most often typical settings, with diverse students, including students at-risk for academic failure, economically disadvantaged students, and students with disabilities. Additionally, applications of explicit instruction incorporate the range of school content areas including reading (decoding and comprehension), mathematics, language arts, history/social studies, science, health, art, and music education.

One of the most visible implementations of direct instruction in public schools is Wesley Elementary in Houston, TX. When the school began implementation of instruction using direct instruction, fifth grade students were almost two years below grade level. After four years of implementation, the third, fourth, and fifth grade students were performing 1 to 1.5 years above grade level. All students scored above the 80th percentile in both reading and mathematics on the district evaluation. Wesley School continues these effective practices school-wide and continues to have exemplary scores on district, state, and national assessments.

It has been thought that teaching using explicit instruction is most beneficial for low-performing students and students in special education. However, the results from extensive research repeatedly indicate that allstudents benefit from well-designed and explicitly taught skills.

Evidence of Effectiveness

A meta-analysis conducted by G. Adams (1996) yielded over 350 publications (articles, books, chapters, convention presentations, ERIC documents, theses, dissertations, and unpublished documents) on various forms of studies conducted on explicit instruction. Criterion for inclusion limited the analysis to 37 research publications that met four groupings: (a) regular education, (b) special education, (c) the National Follow-Through Project, and (d) follow-up studies. Some example findings include—

- In his meta-analysis, Adams found that the mean effect size per study using explicit instruction is more than .75 (effects of .75 and above in education are extraordinary). Accordingly, this confirms that overall effect of explicit instructional practices is substantial. Thirty-two of the 34 studies analyzed had statistically significant positive effect sizes. The authors found the consistent attainment of research with substantial effect sizes is further evidence that explicit instruction is an effective instructional practice for all students. The authors concluded that although direct instruction is often described as a program for students in special education, the effect sizes calculated in this meta-analysis are nearly the same, thus indicating the teaching strategy is effective for students in general education as well as those identified with disabilities.

- National Follow-Through Project: Students receiving explicit instruction in reading, mathematics, language, and spelling achieved well in these basic skills; as well as reading comprehension, problem solving, and math concepts.

- National Follow-Through Project: Student scores were above other treatment conditions in the affective domain as well as the academic. This suggests that competence in school-related skills enhances self-esteem. “Critics of the model have predicted that the emphasis on tightly controlled instruction might discourage children from freely expressing themselves and thus inhibit the development of self-esteem. In fact, this is not the case” (Abt IVB, p. 73).

- Review of the research on beginning reading using explicit instruction strategies reported that students considered disadvantaged and students with diverse needs, like other students, benefit most from early and explicit teaching of word recognition skills, including phonics.

- Carnine and colleagues empirically evaluated effective delivery components essential to explicit instruction to validate each in relation to student outcomes for a range of students by ability and by age.