DI and Implications for UDL Implementation

To differentiate instruction is to recognize students’ varying background knowledge, readiness, language, preferences in learning and interests; and to react responsively. As Tomlinson notes in her recent book Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners(2014), teachers in a differentiated classroom begin with their current curriculum and engaging instruction. Then they ask, what will it take to alter or modify the curriculum and instruction so that so that each learner comes away with knowledge, understanding, and skills necessary to take on the next important phase of learning.

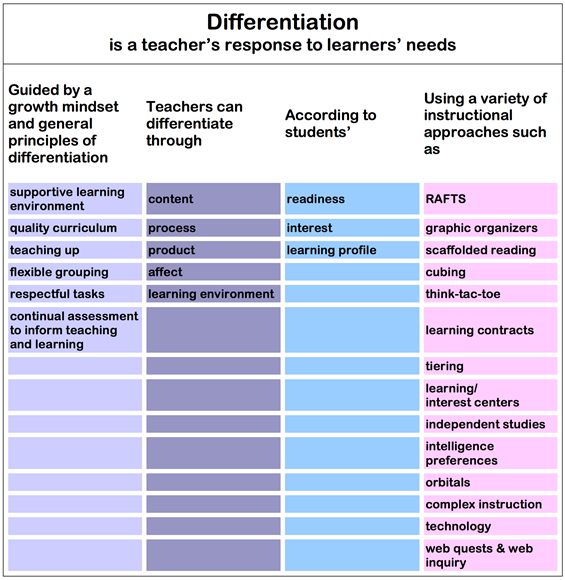

Differentiated instruction is a process of teaching and learning for students of differing abilities in the same class. Teachers, based on characteristics of their learners’ readiness, interest, learning profile, may adapt or manipulate various elements of the curriculum (content, process, product, affect/environment). These are illustrated in Table 1 below which presents the general principles of differentiation by showing the key elements of the concept and relationships among those elements.

Table 1. Principles of Differentiation.

Adapted with permission from Carol Tomlinson: Differentiation Central Institutes on Academic Diversity in the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia (September 2014)

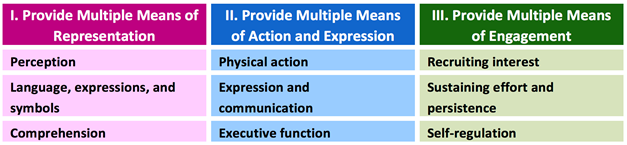

Differentiated instruction is well received as a classroom practice that may be well suited to the principles of UDL. The following section looks at the foundational principles of universal design for learning (UDL): engagement, action and expression, and representation—in order to address the ways in which differentiated instruction coordinates with UDL principles. Certain instructional techniques have been found to be very effective in supporting different skills as students learn. Differentiated instruction is designed to keep the learner in mind when specifying the instructional episode.

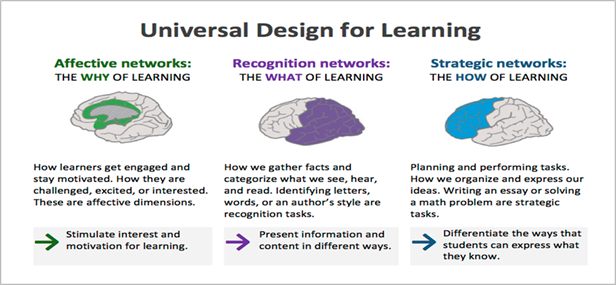

Recognition networks. The UDL principle that focuses on representation and the importance of providing multiple, flexible methods of presentation when teaching indicates that no single teaching methodology for representing information will be satisfactory for every learner. The theory of differentiated instruction incorporates some guidelines that can help teachers to support critical elements of recognition learning in a flexible way and promote every student’s success. Each of the four key elements of differentiated instruction (content, process, product, and affect/environment) supports an important UDL practice for meeting the needs of all learners.

The content guidelines for differentiated instruction support the UDL principle, provide multiple means of representation, in that they encourage the use of several elements and materials to support instructional content. A teacher following this principle might help students in a social studies class to understand the location of a state in the union by showing them a wall map or a globe, projecting a state map, or describing the location in words. Also, while preserving the essential content, a teacher could vary the difficulty of the material by presenting smaller or larger, simpler or more complex maps. For students with physical or cognitive disabilities, such a diversity of examples may be vital in order for them to access the pattern being taught. Other students may benefit from the same multiple examples by obtaining a perspective that they otherwise might not. In this way, a range of examples can help to ensure that each student’s recognition networks are able to identify the fundamental elements characterizing a pattern.

This same use of varied content examples supports a recommended UDL Guideline: provide options for perception. A wide range of tools for presenting instructional content are available, especially in the digital environment; thus teachers may manipulate size, color contrasts, audio, and other features to develop examples in multiple media and formats. These can be saved for future use and flexibly accessed by different students depending on their needs and preferences.

The pillars of differentiated instruction also recommend that content elements of instruction be kept concept-focused and principle-driven. This approach is consistent with the UDL Guideline provide options for language, mathematical expression, and symbols. By avoiding any focus on extensive facts or seductive details and reiterating broad concepts, a goal of differentiated instruction, teachers are highlighting essential components and better supporting recognition networks.

The UDL Guideline provide options for comprehension, and, in this context, the assessment step of the differentiated instruction learning cycle is instrumental. By evaluating student knowledge about a construct before designing instruction teachers can better support students’ knowledge base, scaffolding instruction in a very important way.

Strategic networks. People find for themselves the most desirable method of learning strategies; therefore, teaching methodologies need to be varied. This kind of flexibility is key for teachers to help meet the needs of their diverse students, and this is reflected in the UDL principle provide multiple means of action and expression. Differentiated instruction can support this practice in valuable ways.

Differentiated instruction recognizes the need for students to receive flexible models of skilled performance, which reflects the UDL Guideline provide options for expression and communication. As noted above, teachers implementing differentiated instruction are encouraged to demonstrate information and skills multiple times and at varying levels. As a result, learners enter the instructional episode with different approaches, knowledge, and strategies for learning.

When students are engaged in initial learning on novel tasks or skills, providing graduated support for practice and performance should be used to build fluency, ensure success, and support eventual independence. Supported practice enables students to split up a complex skill into manageable components and fully master those components. Differentiated instruction promotes this teaching method by encouraging students to be active and responsible learners and by asking teachers to respect individual differences and scaffold students as they move from initial learning to practiced, less-supported skills mastery.

In order to successfully demonstrate the skills that they have learned, students need flexible opportunities for demonstrating skill. Differentiated instruction directly supports this UDL checkpoint by reminding teachers to provide multiple options for learning and expressing knowledge, including the degree of difficulty and the means of evaluation or scoring.

Affective networks. Differentiated instruction and UDL bear another important point of convergence: recognition of the importance of engaging learners in instructional tasks. UDL calls for motivating and sustaining learner engagement through flexible instruction, an objective that differentiated instruction supports very effectively.

Differentiated instruction theory reinforces the importance of effective classroom management and reminds teachers of meeting the challenges of effective organizational and instructional practices. Engagement is a vital component of effective classroom management, organization, and instruction. Therefore teachers are encouraged to offer choices of tools, adjust the level of difficulty of the material, and provide varying levels of scaffolding to gain and maintain learner attention during the instructional episode. These practices bear much in common with the UDL principle provide multiple means of engagement by offering choices of content and tools; providing adjustable levels of challenge, and offering a choice of learning context. By providing varying levels of scaffolding when differentiating instruction, students have access to varied learning contexts as well as choices about their learning environment.

Differentiated instruction, like UDL, has been developing in educational settings over the past 20 years. They have both received significant recognition. When differentiation is combined with the practices and principles of UDL, it can provide teachers with both theory and practice to appropriately challenge the broad scope of students in classrooms today. Although educators are continually challenged by the ever-changing classroom profile of students, resources, and reforms, practices continue to evolve and the relevant research base should grow. And along with them grows the promise of differentiated instruction and UDL in educational practices.